|

Drawing from Sculptures and Plaster Casts |

By Dan Gheno

I often tell my students that an

artist’s education doesn’t end with the finish of one’s school years.

For a figurative artist especially, it’s a life long pursuit, observing

and learning about the human form and the landscape, evolving a greater

understanding of our forms and psychology and the settings that surround us. And

whatever your artistic goals---whether you are utilizing the figure for

abstractive, expressive or realistic purposes--- all of this is coupled with the

necessity to constantly exercise your eye-hand coordination, drawing at least a

little bit every day throughout your life, so that you can better translate your

brain and eye’s goals through your hand.

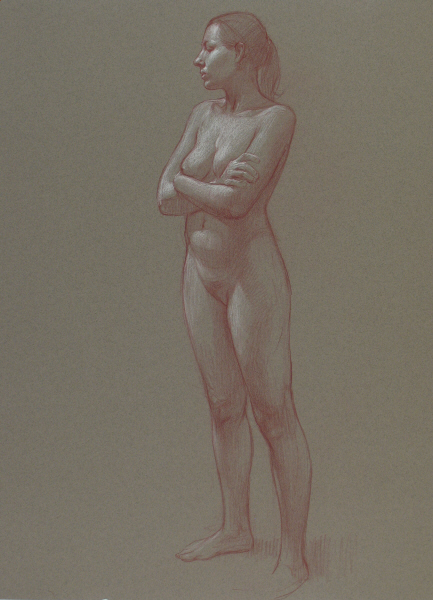

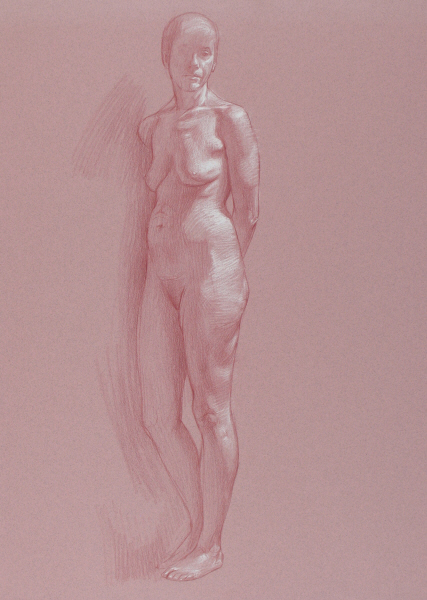

Of course, you have to start some place in your education as an artist. Traditionally, many art academies of the past and present steer their students toward making copies of the masters, first starting with the study of master drawings from reproductions, moving to drawing from plaster casts until, finally, the students graduate to working from life and the living, breathing human form. Although certainly effective, I advocate a less linear approach. I encourage my students to work from life immediately, so that from the very beginning, they feel the gut level passion and excitement that comes from working from a living breathing human being. This way, you also start to experience some of the value, proportion and line problems that are associated with life drawing and painting. Then you can turn to master drawings as a sort of “answer book” to see how the experts solved the same problems you encounter in the studio. And while cast drawing is usually associated with “novices,” many mature artists frequently return to cast drawing to upgrade their understanding of values. Even many of the early artists from the Renaissance and Baroque period did this, drawing from the then recently excavated Greek and Roman statues. I often tell my students to draw from marbles when they have a choice---preferably statues illuminated by a single light source.

Like the plaster cast reproduced here (by Belinda Jouet, student of Kenyon Cox), marble statues are nearly white and devoid of the colors that normally

confuse the artist’s study of values. But

marble sculpture has a decided advantage over plaster casts. Like skin, marble

is slightly translucent, so that light seems to shimmer through the upper

portions of their surfaces. Highlights

and shadow edges will glow on both human and marble surfaces, while on the more

opaque skin of the plaster casts, they will seem flatter, more matte--- and

comparatively lifeless. Nonetheless,

it is still useful to work from plaster casts since they are so readily

available, and they will definitely serve your purposes.

Like the plaster cast reproduced here (by Belinda Jouet, student of Kenyon Cox), marble statues are nearly white and devoid of the colors that normally

confuse the artist’s study of values. But

marble sculpture has a decided advantage over plaster casts. Like skin, marble

is slightly translucent, so that light seems to shimmer through the upper

portions of their surfaces. Highlights

and shadow edges will glow on both human and marble surfaces, while on the more

opaque skin of the plaster casts, they will seem flatter, more matte--- and

comparatively lifeless. Nonetheless,

it is still useful to work from plaster casts since they are so readily

available, and they will definitely serve your purposes.

Remember, life is not confined to the model stand and neither is the discipline of drawing. It’s important to carry your sketch book with you, drawing people wherever you go, in restaurants, on the bus or subway, even from TV if the subject matter is compelling to you. The important thing is to practice always, looking at life, not just as an academic study, but also as a visual quest, gathering information, ideas and inspiration for your more finished paintings, drawings, sculptures and printmaking or as finished works of art in themselves.

Click Here for

PDF of essay as print

Click

Here

to return to

Home Page