Views of Venice

(FROM THE SANTA BARBARA NEWS AND REVIEW, THURSDAY, APR.

5,79)

By Dan Gheno

DURING THE RENAISSANCE, Venice was at the center of a cultural, political and economic flowering that spread throughout Europe. But by the eighteenth century, history was closing in on Venice. It was no longer the main support of European merchant trade; encrusted with a veneer of rich palaces and statues, the canal town was now a city of ignominious tourist trade, an early Disneyland.

But once a merchant town, always a merchant town. Visitors could not only buy a good time, they could also buy a pictorial slice of Venice itself. Artists like Giovanni Antonio Canaletto (1697-1768) produced voluptuous etchings and paintings—fancy postcards for the rich, depicting the beautiful city of water.

Canaletto’s etched vedutes or views of Venice were abundant in his day. His 30 some etchings were sold separately or in volumes, but only a few complete sets remain

William Gumberts, an admirer of Canaletto, spent almost 30 years reassembling the artist’s set of etchings piece by piece. His endeavors finally completed, the collector recently donated the collection to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in honor of local resident Robert M. Light, who helped Gumberts with the detective work. Combined with some borrowed paintings, these graphics form a new exhibition at the museum called "Canaletto Etchings."

Canaletto the Camera

IN THE DAYS before the camera, artists like Canaletto provided the only visual documentation possible and today offer a detailed look at the eighteenth century city. Drawing or painting in a precise, almost unemotional manner, many Venetian artists even used a camera obscura to trace their image. Canaletto used such a device occasionally but only as a guide. Since the artist had spent years doing stage backgrounds with his father, architecture and perspective had already become second nature by the time he began canvas painting.

Canaletto exudes extreme self-confidence in his work, compared to his contemporaries, who often paid slavish

homage to the stiff, unwavering perspective line. Although he certainly can’t be classed an impressionist, his pictures are suffused with a lively mixture of small brushstokes that imitate the flickering light of his hometown. Likewise, his etchings have a shimmering optical quality to the linework that was unusually free for his era.Everything about Canaletto’s approach suggests confident pride in his city, an unquestioning sentiment shared by his compatriots. Even in the middle 1700s when it seemed as though the sea had long forsaken its spouse, Venice was still a city to love, at least for her artists. Lavish ceremonies and carnivals marked Venice’s "Wedding with the Sea," first celebrated in the year 1000 and serving as subject matter for many paintings.

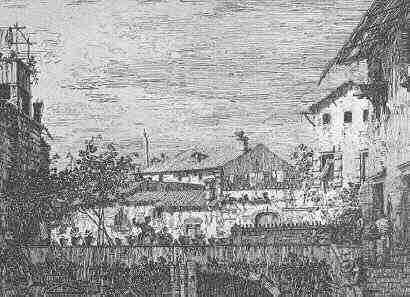

Canaletto’s etchings of Venice.

A carnival is in full swing in Canaletto’s View of the Piazzetta, toward the South. Below the palace of the Duke, citizens and visitors cavort behind masks, garbed in coats of silk and gold. Blocking our view of the waterfront is a large temporary wooden structure that houses even more merry makers inside.

Canaletto painted a particular image of fun and games here. Yet, he was also inadvertently dramatizing a universal image of Venice. Canaletto first painted the background and then the people on top; with the passage of time, his people have turned semi-transparent. They are like ghosts who are still celebrating among the ageless buildings which stand to this day.

Another canvas depicts an ancient city, built on an island of mud and trust. In fact, we almost feel that the sea is trusted more than the people in Le Preson Venice. A Stout, sturdy prison overlooks a calm, almost mirror-like canal in the etching. The broad, flat quay stands delicately above the immense waters, separated only by three brittle thin steps. Prison bars are required for potentially dangerous humans while the sea is held at bay with deep-seated faith.

Foreign Benefactor

Caneletto needed more than faith to live on, and resident painters were not supported by local money. Fortunately, he found a benefactor, Joseph Smith, the British Consul to Venice. Through him, Canaletto received many commissions from the British Empire; in fact the royal collection is said to have the most examples of Canaletto’s work.

Unfortunately, foreign orders almost dried up during the War of the Austrian Secession, which obstructed access to the city. At this point, in the 1740s, Canaletto turned to the etchings presented in the Santa Barbara show.

Canaletto finally pulled up stakes entirely and moved to England in 1746 for 10 years. Yet even there he met critical resistance, as English historian George Vertue points out: "He does not produce work so well as those of Venice or other parts of Italy...His water and his skies at no time excellent or with natural freedom."

Apparently, much of Canaletto’s work became bland, hard to differentiate from the paintings of his nephew. "The painter grew rich, famous, sought after—but also, one suspects, jaded and bored stiff," writes Viscount John Julius Norwich.

Returning to Venice, Canaletto never again personally etched any of his work. He produced 30 drawings for etchings by Giovanni Battista Brustoloni, but these prints have the deadly stiffness common to such copies.

Even so, Canaletto’s paintings speak loudly and are a constant reminder to modern-day Venetians. With the sea encroaching on one side and the acid fumes of Mestre on the other, the faded transparent figures in Canaletto’s compositions serve as a reminder of Venice’s faded glory.

| REVIEW #7 | REVIEW #8 | REVIEW #9 | REVIEW # 10 | |

| REVIEW #12 | REVIEW #13 | REVIEW #14 | REVIEW #15 | |